Forward Compatibility: The Hidden Superpower of Natural Language Programming

Why Playbooks programs automatically get better as LLMs improve - while traditional agent implementations waste money on capabilities they can’t use

Every agent framework promises to make AI development easier. But there’s a question almost no one is asking:

What happens to the agents you build today when better LLMs arrive tomorrow?

The answer exposes a fundamental divide in how we think about AI systems - and why Playbooks represents a genuinely different paradigm.

The Problem No One Talks About

When you build an agent using traditional frameworks like LangGraph, CrewAI, or AutoGen, you’re not just writing application logic. You’re making architectural decisions shaped by the current limitations of LLMs.

Some compensation happens at the framework level - output parsers, retry logic, structured output handling. That’s reasonable. Framework maintainers can update that code, and all agents benefit.

But the real problem lives at the agent implementation level.

To work around what models can’t do reliably today, teams embed compensating structures directly into their agents:

- Intent classifiers that route requests into predefined workflows

- Workflow logic implemented in Python because the LLM can’t be trusted to follow multi-step instructions

- Explicit state machines because the model can’t reliably track progress

- Custom context engineering code tailored to a specific agent and model

- Decomposed micro-tasks because the model can’t handle the full problem end-to-end

- Hard-coded decision trees because judgment isn’t reliable enough

These aren’t framework utilities you can swap out later. They are your agent’s architecture.

And that’s where the trap closes.

The Intent Classifier Ceiling

The intent classifier pattern deserves special attention because it’s everywhere in production systems.

It made sense early on. Models were decent at classification but weak at reasoning, so architects built systems that:

- Classify the user’s request into a known intent

- Trigger a corresponding hard-coded workflow

But this pattern has a hard ceiling.

When a request:

- Spans multiple intents

- Requires synthesis across capabilities

- Involves novel reasoning

- Doesn’t fit neatly into predefined buckets

…the system fails - not because the model couldn’t handle it, but because the architecture never lets the model try.

The LLM’s reasoning ability is effectively bypassed.

Frozen at Yesterday’s Capability Level

Now fast-forward.

A more capable model arrives - one that can reason through novel situations, can follow complex workflows from a description, can maintain state across long interactions.

What happens?

Nothing.

The intent classifiers are still there. The Python workflows are still there. The state machines are still there. The micro-task decomposition is still there.

Your agent is frozen at the capability level of the model it was originally built for.

And here’s the cruel part:

You’re now paying for capabilities your architecture refuses to use.

You upgrade to a better model, but your system still:

- Forces unnecessary multi-call workflows

- Fragments problems the model could solve holistically

- Rejects valid requests that don’t match predefined intents

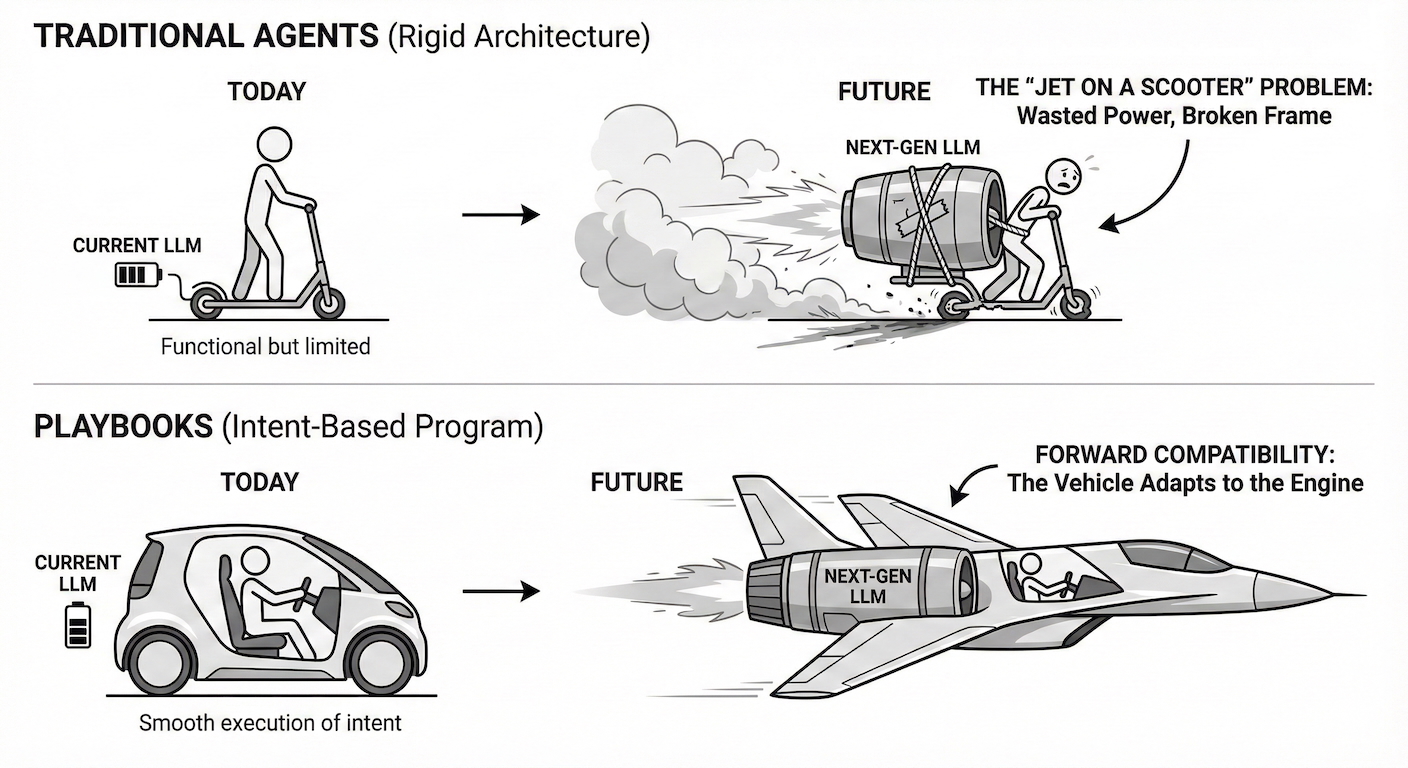

It’s like bolting a jet engine onto a scooter. You pay for supersonic thrust, but the frame, wheels, and steering were designed for a lawnmower motor.

This isn’t just technical debt. It’s ongoing operational waste.

A Real Example: The Nativity Scene

Consider this Playbooks program that orchestrates a multi-agent nativity scene with six characters - each with their own personality, behaviors, and interaction patterns:

# Mary

You are Mary, mother of the Christ child...

## Nativity Meeting

meeting: true

### Steps

- Wait for the Narrator to introduce the scene

- When welcomed by the Narrator, greet the Magi with warmth and humility

- While the meeting is active

- When a Magi presents their gift

- Receive it with grace and gratitude

- Reflect briefly on its meaning for your child

- When Balthasar speaks of sacrifice or sorrow

- Let a shadow pass over your face, for you sense the truth

This program expresses pure intent. It describes what should happen, not how to force a particular LLM to do it.

Here’s the key observation:

- Claude Sonnet 3 could not execute this reliably without significant framework scaffolding - explicit state tracking, careful context shaping, guardrails to keep agents in role.

- Claude Opus 4.5 executes the same program beautifully with minimal framework intervention.

The program didn’t change. Not a single line.

The framework simply had to do less work because the model improved.

The Compiler Analogy

This is exactly how high-level programming languages work.

When you write C code, you don’t rewrite it for every new CPU architecture. The compiler adapts. The same source code runs on radically different hardware, improving automatically as the compiler and processors evolve.

Playbooks programs are source code. The framework is the compiler/runtime. The LLM is the execution substrate.

As the “hardware” improves, the same program runs better - without modification.

Traditional agent frameworks don’t work this way. They’re closer to hand-optimized assembly - tightly coupled to the quirks and limits of the processor they were written for. When the processor changes, you rewrite.

Where the Burden Lives

This difference comes down to where LLM limitations are handled:

| Traditional Frameworks | Playbooks |

|---|---|

| Agent architecture compensates for model limits | Agent architecture expresses pure intent |

| Better models → higher cost, flat returns | Better models → fewer calls, better results |

| Workflow logic lives in Python | Workflow logic lives in natural language |

| Fixed call structure regardless of capability | Call structure adapts to model strength |

| Reimplementation to use new capabilities | Framework adapts, program unchanged |

With traditional frameworks, you absorb model limitations - and those decisions become permanent.

With Playbooks, the framework absorbs them. As models improve, the framework steps out of the way.

What This Means for Enterprise AI

This forward-compatibility advantage has real consequences:

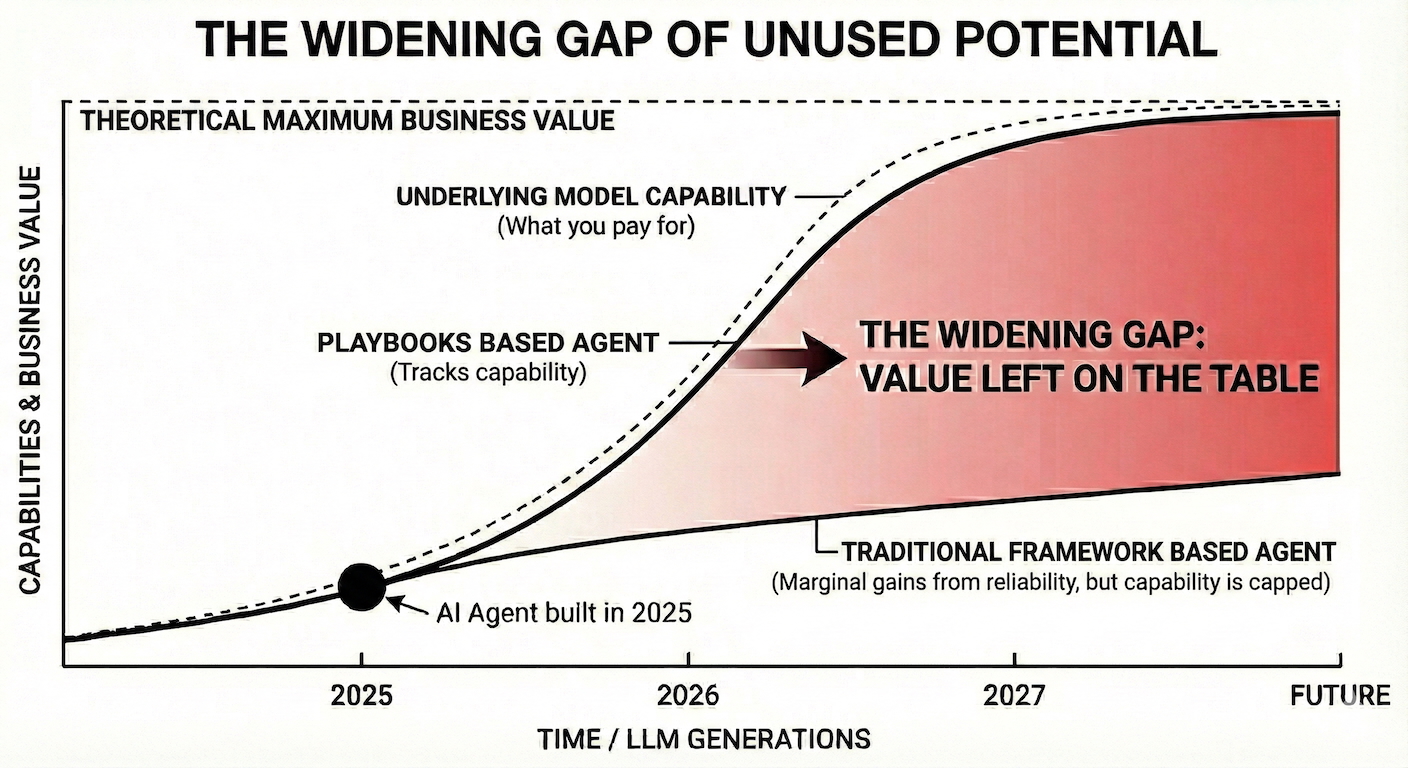

Costs Improve Over Time

Better models mean fewer calls, not wasted capability. You stop paying for intelligence your architecture can’t exploit.

Your Programs Appreciate

Playbooks programs don’t become legacy debt. They gain value as models improve.

No Migration Projects

Upgrading models doesn’t trigger rewrites, re-tuning, or architectural overhauls.

Less Maintenance, More Leverage

Teams focus on intent and business logic - not endless compensating code.

You Can Write Ahead of the Curve

Programs can express intent beyond today’s model limits and simply start working better as capability catches up.

The Widening Gap

Here’s the uncomfortable truth:

As LLMs improve, the cost of not using their capabilities grows.

Traditional agents accumulate architectural debt and operational waste. The better the models get, the more money you spend without seeing proportional gains.

Playbooks programs do the opposite. They get better and cheaper - automatically.

The intent was always correct. Execution just keeps catching up.

The Semantic Abstraction Layer

Playbooks operates at a semantic abstraction layer above raw LLM mechanics.

When you write:

- When Balthasar speaks of sacrifice or sorrow

- Let a shadow pass over your face

You’re not specifying prompts, parsers, or retries. You’re specifying meaning and behavior.

The framework’s job is to realize that meaning on whatever model you’re using. As models improve, less scaffolding is required.

That’s Software 3.0 - not just a new way to build agents, but a new contract between human intent and machine execution.

Try It Yourself

Write a Playbooks program today. Run it across different models. Watch the framework adapt while your program stays the same.

Then imagine what that program will do when next year’s models arrive.

That’s forward compatibility. That’s natural language programming. And that’s why Playbooks is infrastructure for the long term.